Bantu languages: Difference between revisions

(→Origin) |

(→Origin) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

The technical term Bantu, meaning "human beings" or simply "people", was first used by Wilhelm Bleek (1827–1875), as this is reflected in many of the languages of this group. A common characteristic of Bantu languages is that they use words such as ''muntu'' or ''mutu'' for "human being" or in simplistic terms "person", and the plural prefix for human nouns starting with ''mu-'' (class 1) in most languages is ''ba-'' (class 2), thus giving ''bantu'' for "people". Bleek, and later Carl Meinhof, pursued extensive studies comparing the grammatical structures of Bantu languages. | The technical term Bantu, meaning "human beings" or simply "people", was first used by Wilhelm Bleek (1827–1875), as this is reflected in many of the languages of this group. A common characteristic of Bantu languages is that they use words such as ''muntu'' or ''mutu'' for "human being" or in simplistic terms "person", and the plural prefix for human nouns starting with ''mu-'' (class 1) in most languages is ''ba-'' (class 2), thus giving ''bantu'' for "people". Bleek, and later Carl Meinhof, pursued extensive studies comparing the grammatical structures of Bantu languages. | ||

==Classification== | |||

{{main|Guthrie classification of Bantu languages}} | |||

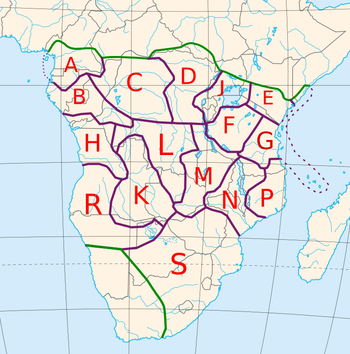

[[File:Bantu zones.png|thumb|350px|The approximate locations of the sixteen Guthrie Bantu zones, including the addition of a zone J around the Great Lakes. The Jarawan languages are spoken in Nigeria.]] | |||

The term 'narrow Bantu' was coined by the ''Benue–Congo Working Group'' to distinguish Bantu as recognized by Malcolm Guthrie in his 1948 classification of the Bantu languages, from the Bantoid languages not recognized as Bantu by Guthrie (1948). In recent times, the distinctiveness of Narrow Bantu as opposed to the other Southern Bantoid groups has been called into doubt (cf. Piron 1995, Williamson & Blench 2000, Blench 2011), but the term is still widely used. A coherent classification of Narrow Bantu will likely need to exclude many of the Zone A and perhaps Zone B languages. | |||

There is no true genealogical classification of the (Narrow) Bantu languages. Most attempted classifications are problematic in that they consider only languages that happen to fall within traditional Narrow Bantu, rather than South Bantoid, which has been established as a unit by the comparative method. The most widely used classification, the alphanumeric coding system developed by Guthrie, is mainly geographic. | |||

At a broader level, the family is commonly split in two depending on the reflexes of proto-Bantu tone patterns: Many Bantuists group together parts of zones A through D (the extent depending on the author) as ''Northwest Bantu'' or ''Forest Bantu'', and the remainder as ''Central Bantu'' or ''Savanna Bantu''. The two groups have been described as having mirror-image tone systems: Where Northwest Bantu has a high tone in a cognate, Central Bantu languages generally have a low tone, and vice versa. | |||

Northwest Bantu is more divergent internally than Central Bantu, and perhaps less conservative due to contact with non-Bantu Niger–Congo languages; Central Bantu is likely the innovative line cladistically. Northwest Bantu is clearly not a coherent family, but even for Central Bantu the evidence is lexical, with little evidence that it is a historically valid group. | |||

The only attempt at a detailed genetic classification to replace the Guthrie system is the 1999 "Tervuren" proposal of Bastin, Coupez, and Mann.<ref>The Guthrie, Tervuren, and SIL lists are compared side by side in [https://web.archive.org/web/20090325021837/http://www.african.gu.se/maho/downloads/bantulineup.pdf Maho 2002].</ref> However, it relies on lexicostatistics, which, because of its reliance on similarity rather than shared innovations, may predict spurious groups of conservative languages that are not closely related. Meanwhile, ''Ethnologue'' has added languages to the Guthrie classification that Guthrie overlooked, while removing the Mbam languages (much of zone A), and shifting some languages between groups (much of zones D and E to a new zone J, for example, and part of zone L to K, and part of M to F) in an apparent effort at a semi-genetic, or at least semi-areal, classification. This has been criticized for sowing confusion in one of the few unambiguous ways to distinguish Bantu languages. Nurse & Philippson (2006) evaluate many proposals for low-level groups of Bantu languages, but the result is not a complete portrayal of the family. ''Glottolog'' has incorporated many of these into their classification.<ref name=Glottolog/> | |||

Nonetheless, some version of zone S (Southern Bantu) does appear to be a coherent group. The languages that share Dahl's Law may also form a valid group, Northeast Bantu. The infobox at right lists these together with various low-level groups that are fairly uncontroversial, though they continue to be revised. The development of a rigorous genealogical classification of many branches of Niger–Congo, not just Bantu, is hampered by insufficient data. | |||

==Language structure== | |||

Guthrie reconstructed both the phonemic inventory and the vocabulary of Proto-Bantu. | |||

The most prominent grammatical characteristic of Bantu languages is the extensive use of affixes (see Sotho grammar and Ganda noun classes for detailed discussions of these affixes). Each noun belongs to a class, and each language may have several numbered classes, somewhat like grammatical gender in European languages. The class is indicated by a prefix that is part of the noun, as well as agreement markers on verb and qualificative roots connected with the noun. Plural is indicated by a change of class, with a resulting change of prefix. | |||

Revision as of 14:54, 28 November 2016

| Bantu | |

|---|---|

| Narrow Bantu | |

| Ethnicity: | Bantu peoples |

| Geographic distribution: | Subsaharan Africa, mostly Southern Hemisphere |

| Linguistic classification: | Niger–Congo

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Bantu |

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5: | bnt |

| Glottolog: | narr1281[1] |

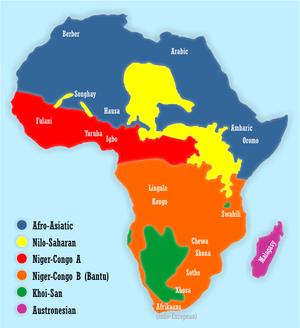

Map showing the distribution of Bantu vs. other African languages. The Bantu area is in orange. | |

The Bantu languages (/ˈbæntuː/),[2] technically the Narrow Bantu languages (as opposed to "Wide Bantu", a loosely defined categorization which includes other Bantoid languages), constitute a traditional branch of the Niger–Congo languages. There are about 250 Bantu languages by the criterion of mutual intelligibility,[3] though the distinction between language and dialect is often unclear, and Ethnologue counts 535 languages.[4] Bantu languages are spoken largely east and south of present-day Cameroon, that is, in the regions commonly known as Central Africa, Southeast Africa, and Southern Africa. Parts of the Bantu area include languages from other language families (see map).

The Bantu language with the largest total number of speakers is Swahili; however, the majority of its speakers know it as a second language. According to Ethnologue, there are over 180 million L2 (second-language) speakers, but only about 2 million native speakers.[5]

According to Ethnologue, Shona is the most widely spoken as a first language,[6] with 10.8 million speakers (or 14.2 million if Manyika and Ndau are included), followed closely by Zulu, with 10.3 million. Ethnologue separates the largely mutually intelligible Kinyarwanda and Kirundi, but, if grouped together, they have 12.4 million speakers.[7]

Estimates of number of speakers of most languages vary widely, due both to the lack of accurate statistics in most developing countries and the difficulty in defining exactly where the boundaries of a language lie, particularly in the presence of a dialect continuum.

Origin

The Bantu languages descend from a common Proto-Bantu language, which is believed to have been spoken in what is now Cameroon in West Africa.[8] An estimated 2,500–3,000 years ago (1000 BC to 500 BC), although other sources put the start of the Bantu Expansion closer to 3000 BC,[9] speakers of the Proto-Bantu language began a series of migrations eastward and southward, carrying agriculture with them. This Bantu expansion came to dominate Sub-Saharan Africa east of Cameroon, an area where Bantu peoples now constitute nearly the entire population.[8][10]

The technical term Bantu, meaning "human beings" or simply "people", was first used by Wilhelm Bleek (1827–1875), as this is reflected in many of the languages of this group. A common characteristic of Bantu languages is that they use words such as muntu or mutu for "human being" or in simplistic terms "person", and the plural prefix for human nouns starting with mu- (class 1) in most languages is ba- (class 2), thus giving bantu for "people". Bleek, and later Carl Meinhof, pursued extensive studies comparing the grammatical structures of Bantu languages.

Classification

The term 'narrow Bantu' was coined by the Benue–Congo Working Group to distinguish Bantu as recognized by Malcolm Guthrie in his 1948 classification of the Bantu languages, from the Bantoid languages not recognized as Bantu by Guthrie (1948). In recent times, the distinctiveness of Narrow Bantu as opposed to the other Southern Bantoid groups has been called into doubt (cf. Piron 1995, Williamson & Blench 2000, Blench 2011), but the term is still widely used. A coherent classification of Narrow Bantu will likely need to exclude many of the Zone A and perhaps Zone B languages.

There is no true genealogical classification of the (Narrow) Bantu languages. Most attempted classifications are problematic in that they consider only languages that happen to fall within traditional Narrow Bantu, rather than South Bantoid, which has been established as a unit by the comparative method. The most widely used classification, the alphanumeric coding system developed by Guthrie, is mainly geographic.

At a broader level, the family is commonly split in two depending on the reflexes of proto-Bantu tone patterns: Many Bantuists group together parts of zones A through D (the extent depending on the author) as Northwest Bantu or Forest Bantu, and the remainder as Central Bantu or Savanna Bantu. The two groups have been described as having mirror-image tone systems: Where Northwest Bantu has a high tone in a cognate, Central Bantu languages generally have a low tone, and vice versa.

Northwest Bantu is more divergent internally than Central Bantu, and perhaps less conservative due to contact with non-Bantu Niger–Congo languages; Central Bantu is likely the innovative line cladistically. Northwest Bantu is clearly not a coherent family, but even for Central Bantu the evidence is lexical, with little evidence that it is a historically valid group.

The only attempt at a detailed genetic classification to replace the Guthrie system is the 1999 "Tervuren" proposal of Bastin, Coupez, and Mann.[11] However, it relies on lexicostatistics, which, because of its reliance on similarity rather than shared innovations, may predict spurious groups of conservative languages that are not closely related. Meanwhile, Ethnologue has added languages to the Guthrie classification that Guthrie overlooked, while removing the Mbam languages (much of zone A), and shifting some languages between groups (much of zones D and E to a new zone J, for example, and part of zone L to K, and part of M to F) in an apparent effort at a semi-genetic, or at least semi-areal, classification. This has been criticized for sowing confusion in one of the few unambiguous ways to distinguish Bantu languages. Nurse & Philippson (2006) evaluate many proposals for low-level groups of Bantu languages, but the result is not a complete portrayal of the family. Glottolog has incorporated many of these into their classification.[1]

Nonetheless, some version of zone S (Southern Bantu) does appear to be a coherent group. The languages that share Dahl's Law may also form a valid group, Northeast Bantu. The infobox at right lists these together with various low-level groups that are fairly uncontroversial, though they continue to be revised. The development of a rigorous genealogical classification of many branches of Niger–Congo, not just Bantu, is hampered by insufficient data.

Language structure

Guthrie reconstructed both the phonemic inventory and the vocabulary of Proto-Bantu.

The most prominent grammatical characteristic of Bantu languages is the extensive use of affixes (see Sotho grammar and Ganda noun classes for detailed discussions of these affixes). Each noun belongs to a class, and each language may have several numbered classes, somewhat like grammatical gender in European languages. The class is indicated by a prefix that is part of the noun, as well as agreement markers on verb and qualificative roots connected with the noun. Plural is indicated by a change of class, with a resulting change of prefix.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lua error in ...ribunto/includes/engines/LuaCommon/lualib/mwInit.lua at line 23: bad argument #1 to 'old_ipairs' (table expected, got nil).

- ↑ "Bantu". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ Derek Nurse, 2006, "Bantu Languages", in the Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics

- ↑ Ethnologue report for Southern Bantoid. The figure of 535 includes the 13 Mbam languages considered Bantu in Guthrie's classification and thus counted by Nurse (2006)

- ↑ Stanford 2013.

- ↑ Lua error in ...ribunto/includes/engines/LuaCommon/lualib/mwInit.lua at line 23: bad argument #1 to 'old_ipairs' (table expected, got nil).

- ↑ Lua error in ...ribunto/includes/engines/LuaCommon/lualib/mwInit.lua at line 23: bad argument #1 to 'old_ipairs' (table expected, got nil).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Philip J. Adler, Randall L. Pouwels, World Civilizations: To 1700 Volume 1 of World Civilizations, (Cengage Learning: 2007), p.169.

- ↑ Genetic and Demographic Implications of the Bantu Expansion: Insights from Human Paternal Lineages Gemma Berniell-Lee et al.

- ↑ Toyin Falola, Aribidesi Adisa Usman, Movements, borders, and identities in Africa, (University Rochester Press: 2009), p.4.

- ↑ The Guthrie, Tervuren, and SIL lists are compared side by side in Maho 2002.