Congo Pedicle: Difference between revisions

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The Congo Pedicle is an example of the arbitrary boundaries<ref>Francis M. Deng: ''Africa and the New World Dis-Order: Rethinking Colonial Borders''. Brookings Review, Vol. 11, Spring 1993</ref> imposed by European powers on [[Africa]] in the wake of the [[Scramble for Africa]], which were "drawn by Europeans, for Europeans, and, apart from a some localized detail, paid scant regard to Africa, let alone Africans."<ref>Ieuan Griffiths: "The Scramble for Africa: Inherited Political Boundaries", ''The Geographical Journal'', Vol 152 No 2, July 1986, pp 204-216.</ref> | The Congo Pedicle is an example of the arbitrary boundaries<ref>Francis M. Deng: ''Africa and the New World Dis-Order: Rethinking Colonial Borders''. Brookings Review, Vol. 11, Spring 1993</ref> imposed by European powers on [[Africa]] in the wake of the [[Scramble for Africa]], which were "drawn by Europeans, for Europeans, and, apart from a some localized detail, paid scant regard to Africa, let alone Africans."<ref>Ieuan Griffiths: "The Scramble for Africa: Inherited Political Boundaries", ''The Geographical Journal'', Vol 152 No 2, July 1986, pp 204-216.</ref> | ||

==Consequences for Northern Rhodesia/Zambia== | |||

As a consequence of Katanga attaining the Pedicle, it gained a toehold in the Bangweulu wetlands and potential mineral resources, although as it turned out, the division of the main copper ore body between the Congo and Northern Rhodesia was determined by the Congo-Zambezi watershed and would not have been affected by the existence or otherwise of the Pedicle. It was the BSAC's failure to get Msiri to sign up Garanganza as a British Protectorate which lost the Congolese Copperbelt to Northern Rhodesia, and some in the BSAC complained that the British missionaries Frederick Arnot and Charles Swan could have done more to help, although their Plymouth Brethren mission had a policy of not being involved in politics.<ref>http://www.dacb.org/stories/demrepcongo/crawford_daniel.html Dr. J. Keir Howard: "Crawford, Daniel" and "Arnot, Frederick", in ''Dictionary of African Christian Biography'', website accessed 7 February 2007</ref> Once Msiri was killed by the CFS it was too late to try again, and consequently the leader of CFS expedition responsible, Canadian Captain William Stairs was viewed by some in Northern Rhodesia as a traitor to the British Empire.<ref>[http://www.nrzam.org.uk ''The Northern Rhodesia Journal'' online], Vol II No 6 (1954) pp67−77. Justice J. B. Thomson: ''Memories of Abandoned Bomas No 8: Chiengi''. Accessed 7 March 2007. The author calls Stairs a 'renegade Englishman' and repeats a rumour that Stairs stole Sharpe's treaty after Msiri had actually signed it, which, while untrue, is indicative of the depth of the feeling in Northern Rhodesia against Stairs.</ref> | |||

===Strategic issues for Zambia=== | |||

The problems for Zambia did not emerge for another 50 years, with the Katanga crisis of 1960-63. The Pedicle cuts off the [[Luapula Province]] and the western part of the [[Northern Province, Zambia|Northern Province]] from the country's industrial and commercial hub of the [[Copperbelt]]. This is exacerbated by the fact that at the Pedicle's toetip, where the Luapula ostensibly flows out of the Bangweulu system, the river swamps are at least 6 km wide and the floodplain is 60 km wide,<ref name="Google"/> making a road impossible with the resources available for most of the 20th century. The most southerly road possible into Luapula keeping to Zambian territory was pushed, by these circumstances, another 200 km north, going around Lake Bangweulu. | |||

Strategically the Congo Pedicle is an issue for Zambia, though not for DR Congo. As well as affecting communication for about one-quarter of the country with the centre and west, it potentially exposes a greater part of Zambia, which has generally enjoyed peace for more than 100 years, to conflict in Katanga, which has not. Zambia has witnessed violence in Katanga between armed factions and by the military against civilians which occasionally has spilled over into Zambia, or which has affected Zambians travelling on the Pedicle road.<ref> Mwelwa C. Musambachime: "Military Violence against Civilians: The Case of the Congolese and Zairean Military in the Pedicle 1890–1988". ''International Journal of African Historical Studies'', Vol. 23, No. 4 (1990)</ref> At times, it has been closed to them making the huge detour around the north and east of Bangweulu the only option. Secondly, cross-border crime and arms smuggling has been a problem in the Copperbelt, as has poaching in the Bangweulu wetlands.<ref>http://timesofzambia.com.zm ''Times of Zambia'' website accessed 6 February 2007.</ref> | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 13:29, 26 July 2017

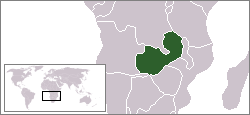

The Congo Pedicle (at one time referred to as the Zaire Pedicle; in French

, meaning ‘Katanga boot’) refers to the southeast salient of the Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo which sticks into neighbouring Zambia, dividing it into two lobes. 'Pedicle' is used in the sense of 'a little foot'. 'Congo Pedicle' or 'the Pedicle' is also used to refer to the Congo Pedicle road which crosses it.

The Congo Pedicle is an example of the arbitrary boundaries[1] imposed by European powers on Africa in the wake of the Scramble for Africa, which were "drawn by Europeans, for Europeans, and, apart from a some localized detail, paid scant regard to Africa, let alone Africans."[2]

Consequences for Northern Rhodesia/Zambia

As a consequence of Katanga attaining the Pedicle, it gained a toehold in the Bangweulu wetlands and potential mineral resources, although as it turned out, the division of the main copper ore body between the Congo and Northern Rhodesia was determined by the Congo-Zambezi watershed and would not have been affected by the existence or otherwise of the Pedicle. It was the BSAC's failure to get Msiri to sign up Garanganza as a British Protectorate which lost the Congolese Copperbelt to Northern Rhodesia, and some in the BSAC complained that the British missionaries Frederick Arnot and Charles Swan could have done more to help, although their Plymouth Brethren mission had a policy of not being involved in politics.[3] Once Msiri was killed by the CFS it was too late to try again, and consequently the leader of CFS expedition responsible, Canadian Captain William Stairs was viewed by some in Northern Rhodesia as a traitor to the British Empire.[4]

Strategic issues for Zambia

The problems for Zambia did not emerge for another 50 years, with the Katanga crisis of 1960-63. The Pedicle cuts off the Luapula Province and the western part of the Northern Province from the country's industrial and commercial hub of the Copperbelt. This is exacerbated by the fact that at the Pedicle's toetip, where the Luapula ostensibly flows out of the Bangweulu system, the river swamps are at least 6 km wide and the floodplain is 60 km wide,[5] making a road impossible with the resources available for most of the 20th century. The most southerly road possible into Luapula keeping to Zambian territory was pushed, by these circumstances, another 200 km north, going around Lake Bangweulu.

Strategically the Congo Pedicle is an issue for Zambia, though not for DR Congo. As well as affecting communication for about one-quarter of the country with the centre and west, it potentially exposes a greater part of Zambia, which has generally enjoyed peace for more than 100 years, to conflict in Katanga, which has not. Zambia has witnessed violence in Katanga between armed factions and by the military against civilians which occasionally has spilled over into Zambia, or which has affected Zambians travelling on the Pedicle road.[6] At times, it has been closed to them making the huge detour around the north and east of Bangweulu the only option. Secondly, cross-border crime and arms smuggling has been a problem in the Copperbelt, as has poaching in the Bangweulu wetlands.[7]

See also

References

<templatestyles src="Reflist/styles.css" />

- ↑ Francis M. Deng: Africa and the New World Dis-Order: Rethinking Colonial Borders. Brookings Review, Vol. 11, Spring 1993

- ↑ Ieuan Griffiths: "The Scramble for Africa: Inherited Political Boundaries", The Geographical Journal, Vol 152 No 2, July 1986, pp 204-216.

- ↑ http://www.dacb.org/stories/demrepcongo/crawford_daniel.html Dr. J. Keir Howard: "Crawford, Daniel" and "Arnot, Frederick", in Dictionary of African Christian Biography, website accessed 7 February 2007

- ↑ The Northern Rhodesia Journal online, Vol II No 6 (1954) pp67−77. Justice J. B. Thomson: Memories of Abandoned Bomas No 8: Chiengi. Accessed 7 March 2007. The author calls Stairs a 'renegade Englishman' and repeats a rumour that Stairs stole Sharpe's treaty after Msiri had actually signed it, which, while untrue, is indicative of the depth of the feeling in Northern Rhodesia against Stairs.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGoogle - ↑ Mwelwa C. Musambachime: "Military Violence against Civilians: The Case of the Congolese and Zairean Military in the Pedicle 1890–1988". International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 23, No. 4 (1990)

- ↑ http://timesofzambia.com.zm Times of Zambia website accessed 6 February 2007.